Warhol Does Beirut

Today’s Beirut has room for Andy Warhol – and Marilyn Monroe. Warhol’s draw to the hedonistic party life and Monroe’s iconicity is akin to the sensibility of the popular culture of Beirut. Though, according to international art collector and curator Emmanuel Javogue, Beirut is like an amalgam of Beijing, Mexico City and San Jose – “an explosion” of how we look through a globalized lens.

Javogue, who fell in love with Beirut for its “generosity and hospitality,” has brought, for the first time in history, the 10-piece set of Warhol’s colorful 1967 silkscreen prints of Monroe’s face to Q Contemporary, an art space which focuses on art promotion rather than sales. Owner Motaz Kabbani finds a parallel in the representation between the presence of Warhol’s work in Beirut in the midst of regional uncertainty and Warhol’s Silver Factory days during the Vietnam War. In other words, there is comfort in celebrating humanity and art in times that seem anything but humane.

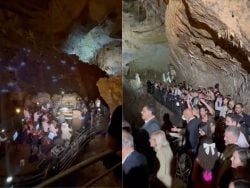

To celebrate the third anniversary of Q Contemporary, the art space invoked Warhol’s famous Silver Factory with wall-to-wall tin-foil, Warhol’s “reality” films, a long couch, a DJ (Beirut’s Jade) and black and white pictures from those infamous days. Even Edie Sedgwick, Warhol’s longtime muse, was reproduced in the form of Q’s art curator, Liv Baggan, who dressed the glamorous part. The Silver Factory (1962-1984), Warhol’s New York City studio, was actually a space where his famous silkscreens were produced in large quantities with the help of artist friends. This was also the place where his radical films of he and his friends partaking in drug use and graphic sex were recorded. In addition to contemporary artists of the time, The Factory hosted the likes of Bob Dylan, Truman Capote, Salvador Dali, and Allen Ginsberg. Warhol’s work and lifestyle were responses to the flourishing sexual revolution of the 60’s, corporate America, and the iconization of celebrities.

In contrast, Tuesday night’s “Factory” opening had strict rules posted on the wall: “No Sex” and “No Drugs” and hosted a middle-aged silk-stocking crowd at 7 p.m., and a younger hip crowd after 9. While the decadent Warhol films showed, the most hedonistic activities were the huddled crowds outside smoking and the delectable tastes of Jai’s catering. Six-hundred people showed up, which certainly was considered a success to the organizers who were thrilled to bring Warhol to Beirut for the first time, and what Baggan considers “the biggest thing” Q has done. Nonetheless, opinions of the exhibit varied.

“With all that’s happening, they bring Warhol to Lebanon,” one woman commented ironically.

Others grinned happily for pictures in front of the art.

Some people thought they looked like fakes.

A famous Lebanese artist who was present claimed he was “opposite of everyone,” balking at the absurdity of Warhol, who he claims to have met in New York City, as well as complaining about the work’s exorbitant worth.

When Beirut.com asked Javogue, who sold much of his beloved art years ago to purchase this set, which he claims are “hard to come by” even in the collector’s world, how much he paid for them, he shook his head. “It doesn’t matter. I don’t like to focus on how much they cost. They’re worth more than money.”

Javogue and Kabbani have similar reasons for bringing Warhol’s work to Beirut. The opportunity to share the art with what Javogue believes to be a society that is “trying hard in difficult times” made Beirut a place he wanted to “inspire” with his collection. Whereas Kabbani strives for a transversal space where he wishes to attract diverse segments of society to appreciate art together – and bring “solace” in troubled times.

But also, it was a matter of serendipity. Swiss bank Director Nabil Jean Sab, whose bank Compagnie Privee de Conseils et d’Investessements S.A. sponsored the exhibit, was the liaison between Javogue and Kabbani, both longtime friends of his. He feels that that the exhibit “fell into place” and was meant to be. As for future exhibitions of the sort, he says “Inshallah… I prefer to spend my time promoting art in Lebanon.”

Warhol’s images are recognizable anywhere, taken for granted. However, standing in front of this original collection hanging solely in this transportation of time and space, is powerful. Kabbani, who is Syrian, is aware of the contrast between the glamorous world that Warhol’s work invokes and the bloody reality in the region. However, in the artwork, one may find the mutable shades of a pop icon, Monroe’s humanity, made real in this inhuman representation. In a city renown for this dichotomy, it seems like a good fit.

The exhibit, whose next stop is Mexico, will remain in Beirut until Saturday, November 24.