Blog

Kamal Jumblatt Did Yoga Before it Was Cool, And Other Things You Didn’t Know About the PSP Founder

Kamal Jumblatt was the founder of the Progressive Socialist Party in Lebanon. He was assassinated in his car during Lebanon’s Civil War. His son, Walid Jumblatt is still a major player in Lebanon’s political scene today. All these facts are pretty well known — plus or minus some tidbits you may have heard from family members and friends over the years.

But now Lebanese audiences have the opportunity to revisit the Druze leader’s legacy – and what he might have meant for the country had he lived – with a new film called, “Kamal Jumblatt, witness and martyr,” now showing in Lebanon. The film is directed by Hady Zaccak, a professor at USJ who has dedicated his career to making movies about Lebanese history.

“The film is not really a film about the past,” Zaccak said in an interview. “It’s also a film about the present.”

Throughout his life, Jumblatt wrote extensively about the problems facing Lebanon and the Arab world. His writings on issues of religious extremism and social inequality – which are featured throughout the film — feel as timely today as when Jumblatt wrote them.

To Zaccak, Kamal Jumblatt represents a utopian dream – the alternate path that Lebanon could have taken toward a secular government, rather than the sectarian system currently in place. Jumblatt is one of the few figures of Lebanese history that could be considered a “father” of the country – and not simply the leader of one small sect or community. In turn, his assassination meant the end of the secular dream for the country.

“Since [the time of] his assassination, there has been the destruction of any national secular models, and we’ve been living more and more in a catastrophe not only in Lebanon but throughout the Arab world,” Zaccak said. “Let us see today what’s happening in Iraq and Syria and Lebanon.”

Zaccak was approached to make the film a few years ago by the Friends of Kamal Jumblatt Association, a cultural institution dedicated to preserving Jumblatt’s legacy. Zaccak was intrigued, but told them “I’m not going to make a propaganda film.” It was important to Zaccak to show Jumblatt’s complexity and human-ness; that he made mistakes.

In fact it was Jumblatt’s complexity that drew Zaccak to him as a character. He drove from Lebanon to India and went on a spiritual journey with a guru there. His first trip was in the 1950s – way, way before the Beatles ever went there. He reserved every morning from 5 am until 9 am for meditation and writing.

At the same time, he came from a very high social position and maintained his wealth throughout his life. He lived in a stately home, leading some of his detractors labeled Kamal Jumblatt the “master of the castle” to poke fun at his progressivism. How could a progressive leader live in a fancy house? (For his part, Jumblatt would counter that Karl Marx and other leaders also came from wealthy families).

And, unlike other socialist leaders of the time, Jumblatt was extremely spiritual. He grew up Druze and studied Christianity and Islam later in life. He thought that socialism needed to return to its spiritual roots. Still, he was willing to use violence to achieve his ends.

All of these complexities and contradiction make Jumblatt, for Zaccak, a “modern Don Quixote” – an idealistic fighter until the very end.

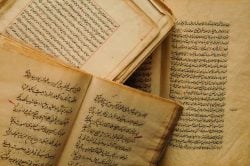

As part of the filming, Zaccak interviewed Walid Jumblatt extensively. The younger Jumblatt appears in interviews throughout the film, showing viewers his father’s belongings, even bloodied books that were with him when he was shot. Jumblatt says that he was “baptized in blood” – his father, as well as his grandfather were both assassinated.

One of the film’s most powerful scenes occurs while Walid Jumblatt discusses his father’s assassination and the brutal massacre of Christians the occurred afterward, as a reprisal. Jumblatt seems to exhibit a real sadness for what happened – a rare acknowledgement of past crimes in a nation ruled by former warlords. After shooting this scene, Zaccak said, he knew he wanted to push forward on the film.

The teaching of history has always been lacking in Lebanon – you may find your own school’s history textbooks ended in 1947, with no mention of the civil war or other conflicts that followed. Zaccak hopes to write the history through films like Kamal Jumblatt, as well as previous films like “A Lesson in History,” “Mercedes,” and “Honeymoon 58,” which is about the war of 1958.

If you want to learn more about a fascinating character – and what could have been in Lebanon, check out Kamal Jumblatt, Witness and martyr, now playing at Empire Dunes.

But now Lebanese audiences have the opportunity to revisit the Druze leader’s legacy – and what he might have meant for the country had he lived – with a new film called, “Kamal Jumblatt, witness and martyr,” now showing in Lebanon. The film is directed by Hady Zaccak, a professor at USJ who has dedicated his career to making movies about Lebanese history.

“The film is not really a film about the past,” Zaccak said in an interview. “It’s also a film about the present.”

Throughout his life, Jumblatt wrote extensively about the problems facing Lebanon and the Arab world. His writings on issues of religious extremism and social inequality – which are featured throughout the film — feel as timely today as when Jumblatt wrote them.

To Zaccak, Kamal Jumblatt represents a utopian dream – the alternate path that Lebanon could have taken toward a secular government, rather than the sectarian system currently in place. Jumblatt is one of the few figures of Lebanese history that could be considered a “father” of the country – and not simply the leader of one small sect or community. In turn, his assassination meant the end of the secular dream for the country.

“Since [the time of] his assassination, there has been the destruction of any national secular models, and we’ve been living more and more in a catastrophe not only in Lebanon but throughout the Arab world,” Zaccak said. “Let us see today what’s happening in Iraq and Syria and Lebanon.”

Zaccak was approached to make the film a few years ago by the Friends of Kamal Jumblatt Association, a cultural institution dedicated to preserving Jumblatt’s legacy. Zaccak was intrigued, but told them “I’m not going to make a propaganda film.” It was important to Zaccak to show Jumblatt’s complexity and human-ness; that he made mistakes.

In fact it was Jumblatt’s complexity that drew Zaccak to him as a character. He drove from Lebanon to India and went on a spiritual journey with a guru there. His first trip was in the 1950s – way, way before the Beatles ever went there. He reserved every morning from 5 am until 9 am for meditation and writing.

At the same time, he came from a very high social position and maintained his wealth throughout his life. He lived in a stately home, leading some of his detractors labeled Kamal Jumblatt the “master of the castle” to poke fun at his progressivism. How could a progressive leader live in a fancy house? (For his part, Jumblatt would counter that Karl Marx and other leaders also came from wealthy families).

And, unlike other socialist leaders of the time, Jumblatt was extremely spiritual. He grew up Druze and studied Christianity and Islam later in life. He thought that socialism needed to return to its spiritual roots. Still, he was willing to use violence to achieve his ends.

All of these complexities and contradiction make Jumblatt, for Zaccak, a “modern Don Quixote” – an idealistic fighter until the very end.

As part of the filming, Zaccak interviewed Walid Jumblatt extensively. The younger Jumblatt appears in interviews throughout the film, showing viewers his father’s belongings, even bloodied books that were with him when he was shot. Jumblatt says that he was “baptized in blood” – his father, as well as his grandfather were both assassinated.

One of the film’s most powerful scenes occurs while Walid Jumblatt discusses his father’s assassination and the brutal massacre of Christians the occurred afterward, as a reprisal. Jumblatt seems to exhibit a real sadness for what happened – a rare acknowledgement of past crimes in a nation ruled by former warlords. After shooting this scene, Zaccak said, he knew he wanted to push forward on the film.

The teaching of history has always been lacking in Lebanon – you may find your own school’s history textbooks ended in 1947, with no mention of the civil war or other conflicts that followed. Zaccak hopes to write the history through films like Kamal Jumblatt, as well as previous films like “A Lesson in History,” “Mercedes,” and “Honeymoon 58,” which is about the war of 1958.

If you want to learn more about a fascinating character – and what could have been in Lebanon, check out Kamal Jumblatt, Witness and martyr, now playing at Empire Dunes.