Why Edward Said hated Omar Sharif’s Guts

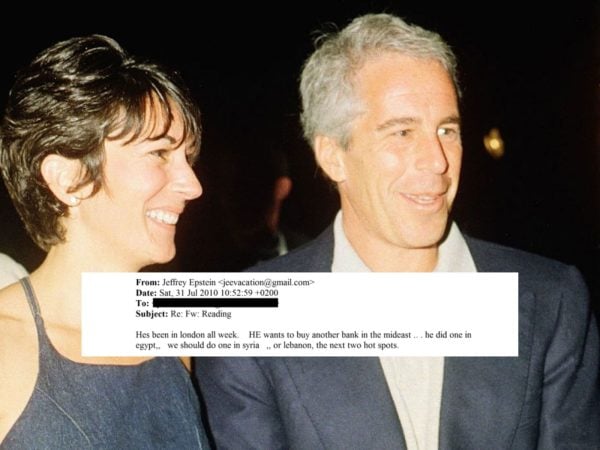

While Lawrence of Arabia fans the world over mourned the passing of actor Omar Sharif earlier this week, at least one of his former acquaintances might be spitting on his grave. That is, if he weren’t already dead himself.

Edward Said was classmates with Omar Sharif in Egypt, back when Sharif, whose parents were Syrian and Lebanese, was still called Michel Shalhoub. As Edward Said recounts in his memoir Out of Place, both attended the elite Victoria College in Cairo, run by the Brits, which was something of an anachronism in Egypt at that time. Outside the school’s walls, the British colonial mandate was on its way out; they struggled to dominate the Suez Canal against Egyptian guerilla fighters. Inside the school, non-British students learned British history, spoke English only, and were divided into “houses… which further inculcated and naturalized the ideology of empire,” Said wrote.

For Said, it was an early encounter with the intellectual and social themes he would later dissect in Orientalism. The British teachers looked down on the Arab students, banned Arabic, and beat them for any minor offense. But young Said defied authority wherever he could – he spoke Arabic with his classmates purely to piss the teachers off and, like a sullen teen, gave ironic answers when called on, “an attitude I regarded as a form of resistance to the British.” The school was about de-Arabizing the Arabs, and Said was having none of it.

By contrast, you have Said’s classmate Omar Sharif – then Michel Shalhoub. Said describes him as “notorious for his stylish brilliance and his equally stylish and inventive coercive dealings with the smaller boys.” Translation: young Omar Sharif was a well-dressed psychopath.

Sharif was your prototypical brownnoser. On free dress days, he wore a white carnation in his lapel, while the rest of his classmates were dressed like the scruffy boys they were. Said describes one episode in which he and another classmate teased Sharif for his clothing, and in response, Sharif nearly broke the classmate’s arm. Why was he doing this, the classmate cried out?

“Because, frankly, I enjoy it,” young Sharif says, like a real psychopath.

Sharif wasn’t just a well-dressed bully, he also sucked up to authority. When a contingent of important British officials came, he gave what Said describes as a majorly ass-kissing speech about the school’s fantastic British education and how lucky the boys were to be graced by the officials present.

Translation: he was the worst.

To Said, Sharif embodied the school’s “entrenched authoritarianism” – a traitor to his fellow Arabs, and one of the worst things about imperialism – a process Said would later dissect in his most famous work Orientalism. Not only was the British ideology produced by the ruling classes, it was then reproduced and internalized by the likes of Sharif. No wonder, then, that Shalhoub later changed his name to something that “Occidentals” would have no trouble remembering, and played the star Arab in one of the most famously Orientalist films of the 20th century, Lawrence of Arabia.

Said says that as a Palestinian man growing up in Egypt following the Nakba, he himself never really fit in wherever he went. However, he ultimately concludes that it was this constantly feeling “out of place” that inspired his own work. “With so many dissonances in my life I have learned actually to prefer being not quite right and out of place.”