The Coffeeshops Of “Abadayet” Old Beirut: Here Are Their Stories

Who were the abadayet of Beirut and what were their coffee shops like? Step back in time with us to one of the most beautiful eras in Beirut’s history and explore the tales of abadayet and their coffee shops in a new episode of our Beirut’s Collective Memory series with the unmatched narrator Tarek Kawa!

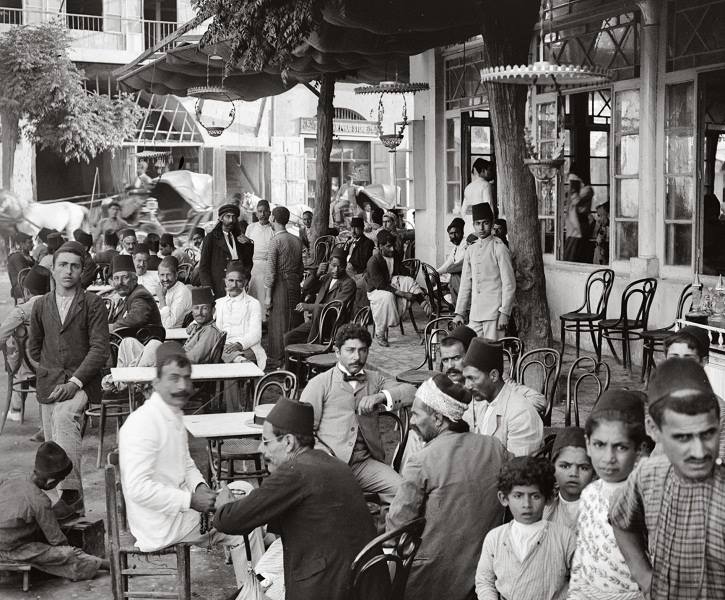

A cafe owned by an abaday was not like any regular cafe owned by an ordinary person; the atmosphere was different, its patrons were different, its walls were immaculately painted…

For instance, all the Basta’s cafes were either supporters of or owned by Saeb Salam and therefore, they were not just regular cafes, they were election centers for Salam… with his photo always plastered on the wall. Another example was Michel Saliba’s cafe in Mazraa which was closely aligned with Henri Pharaoun, and always with Pharaoun was Naseem Majdalani. Similarly, Ahwet el Gemmayze was established and owned by the abaday Al-Osta Baz, and it was considered to be in Pierre Gemayel’s favor.

And the cafe that wasn’t owned by an abaday was mostly a cafe that supported the winner: election seasons would come, a new person’s photo would be plastered up and if he succeeds, they’d keep his picture up, if he fails… they’d remove the picture. The rest of the time, it was all about which horse was primed to win the race, what were the instructions for Sunday? Who was the jockey and who knew him? Unlike the abaday’s cafe, It would be a hub for races and betting all year round.

The service at the abaday‘s cafe was also something else, especially if a personal guest of the abaday was visiting. The guest would be either someone seeking a favor or another abaday from a different area coming to introduce himself or pay respects. Now, depending on who was visiting the cafe, people would know whether or not he was close to the abaday. If he was a friend, most of the patrons would stand to greet him, then they would back off to give them privacy. The service also completely changed when the abaday had a visitor: the brand new tea cups would come out, a fancy copper jug and a shiny new tray, a cup filled with hot water alongside the tea to keep the cup itself warm…all of that and more. And the menu, which at the time was a tiny chalkboard, was immediately hidden when a distinguished guest would arrive.

Let’s return to our topic of abadayats: among them was a very well-known man named Elias Al-Halabi. Now, Elias Al-Halabi was different from the rest of the abadays because it was said that he was responsible for the death of forty men. But it is important to mention that these forty men were not normal people, they were either criminals, thieves, spies, or even perpetrators. So, they considered Elias Al-Halabi to be the vigilante of the abadays, taking revenge and the law into his own hands.

Halabi was known to be noble, generous, extremely handsome, tall, tanned… famous for his mustache that “a falcon could perch on”.

Of the many tales about Al Halabi, it was said that he once discovered someone who was an agent for the French army, working to give them news about the rebels. He managed to capture him in Mazraa and carried out a public trial which ended with the spy’s execution. Another time, he was having a late night at Ahwet Saliba in Mazraa when he heard. He was one of the many abadays who, the more news of him circulated, the more the stories were exaggerated.

But even his death was marked by a strange incident, with people saying that he helped them both during his life and during his death. Here’s what happened: since Halabi was well loved by the masses, many attended his funeral. And when his procession passed by Kahwet Kawkab al Sharq, people who were inside the cafe stepped out to show respect for him.

At that moment, the building collapsed and killed 40 people. Those who stepped out to meet his funeral procession felt saved by him. Similar to Halabi, there were many abadays whose stories are still circulated.

We cannot deny that abadayet were part of Beirut’s life, part of the solutions to the problems at the time, and sometimes they were the problem themselves…but the solution more often.

Do you have stories or anecdotes to share about Old Beirut? Email us!

collective-memory@beirut.com

And I wanted to send a list of some of the many abadayat who ran Beirut in those days:

Basta

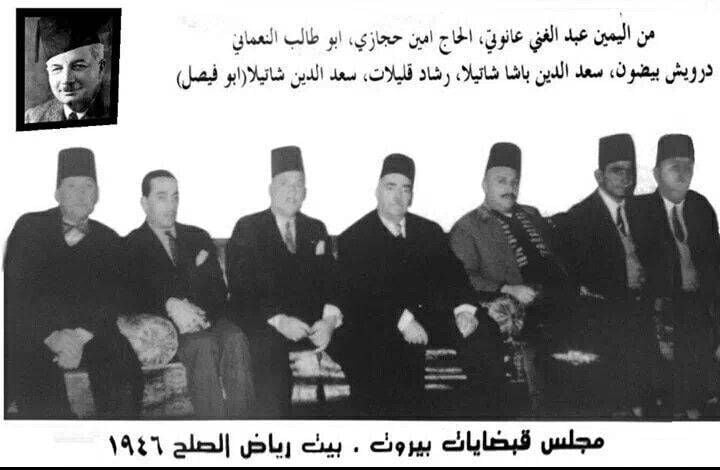

Ibrahim Zeidan, Muhieddine Ja’ana, Salim Al Dana, Abbas Baydoun, Abdullah and Abu Omar Hamida, Abu Ma’ruf Doughan, Abu Adnan Itani, Khalil and Usman Abdul Al, Tawfiq and Salim Al Srouji, Abu Faisal and Saadedine Shatila, Amin Hijazi, Amin Sardouk, Ahmed Safsoof, Abu Afif Kreidieh, Mohammad Samsama, Rashid and Farouq Chehabeddine, Abu Said Al Jannoun

Mousaytbeh

Abdullah Adwan, Khodr Al Fil, Abu Ali Aitour, Mohammad Khodr Al Anouti, Saleh Al Zareef, George Al Azrak, Abu Ahmad Aitour, Rashid Koleilat, Obeido Al Ankidar (Al Sharqawi), Omar Bawab, Khalil Abdulal, Husni Kheriro (Eido), Abu Afif Baadrani, Hussein Eitour, Abu Zuhair Al Fayoumi, Ukeif Al Saba

Ras el Nabeh

Saad al-Din Kaissi, Abu Khalil Dandan

Tareek el Jdeedeh

Abu Maroof Bakdash , Abu Rashid and Rashid Doughan, Jameel Rawwas, Abu Talib Al Naamani, Abdul Rahman Al Dana, Rashed Houri, Saleh Makkouk, Othman Al Hallak, Salim Madhoun, Jameel Hashash, Hajj Said Hamad

Mazraa

Elia Dada, Michel Saghiyeh, George Tadros, Tanios Khalidi, Karim Baki, Nicolas Karam, Mitri Al-Aqdah, Hanna Yazbek, Nakhle Majdalani (Abu Al-Saad), Saliba Majdalani, Elias Al-Halabi, Michel Saliba

Ashrafieh

Hajj Nicola Murad, Paul Nakhla Al-Arbaniyye, Shakir and Elias Nakad, Al-Osta Baz

Horsh

Noor Al-Arab

To join the WhatsApp group that started it all and to tune in to more beautiful Beirut stories, click here

Join Group on WhatsApp

Sharing these stories would not have been possible without the work of following historians and researchers. If not for them and many others, Beirut’s heritage and history would have been lost. A special thanks goes out to:

Louis Cheikho – Taha Al Wali – Nina Jedejian – Hassan Hallak – Suheil Mneimneh – Abdul Lateef Fakhoury – Ziad Itani – Beirut Heritage Society – Ya Beyrouth Page