A Look At The History Of Publishing In Lebanon

Though many attribute Beirut to being an epicenter for publishing in the Arab World during the mid-20th century, the history of publishing in Lebanon began long before that. We decided to journey through the rich history of media in Lebanon, touching on its early beginnings and the tenacity of the Lebanese publishing industry over the years.

Early beginnings in the Ottoman Empire

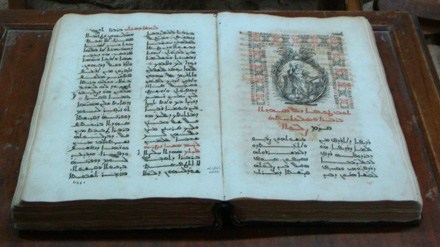

During the 17th century, Christian monks were responsible for a handful of tasks, including the copying, printing, and bookmaking of religious texts (mostly in Syriac). Religious books printed in the Arabic language were initially imported from Italy.

Source: 365 Days of Lebanon.

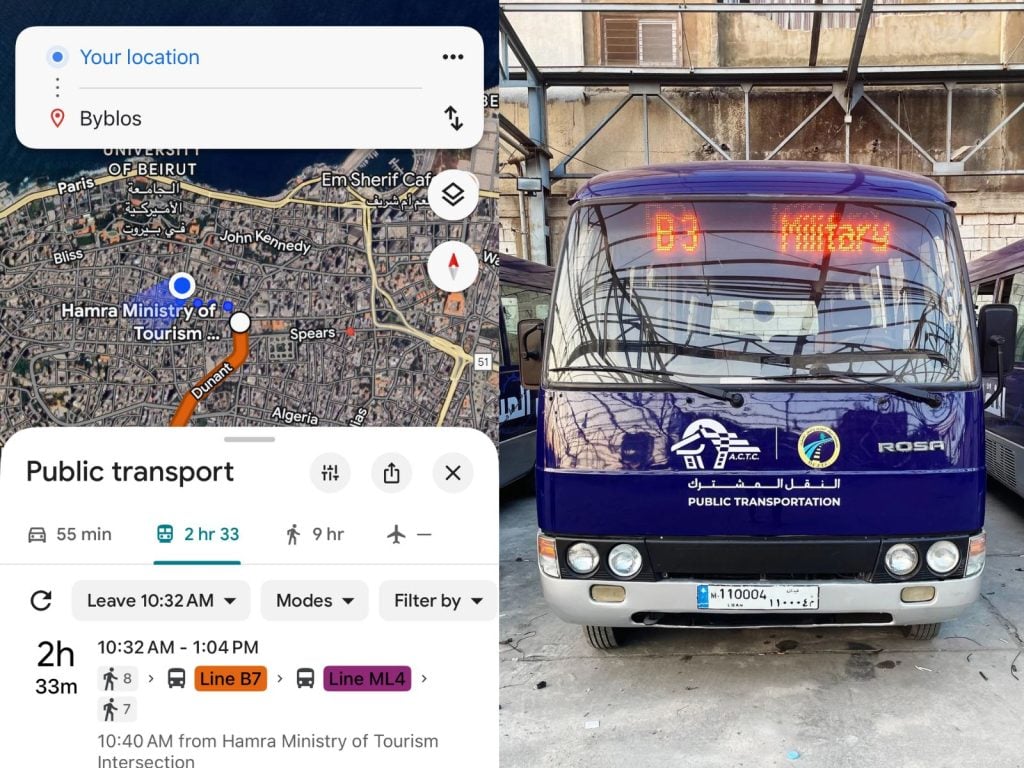

After the first printing press found its way to the region in 1610, located in Mar Anonios Qozhaya, two others appeared in later years, in the Monastery of Saint John Sabigh in 1734 and the Saint George’s Press of Beirut in 1751.

Source: Flickr.

Though many printing presses were operating in earlier periods, books were not published in Arabic in the Arab regions of the Ottoman Empire before 1727, when the ban on it was lifted. The press of Saint John Sabigh was built by Deacon Abdallah Zakhir, operating as the first Arabic printing press in the region. Over the years, Lebanon quickly became a hub for publishing works in Arabic.

The Nahda

Among the first cultural associations appeared in Beirut in the late 19th century, founded by Ibrahim al-Yazigi, Butrus al-Bustani and Mikha’il Mashaqqa. “The deliberations of the society, collected and published by Bustani, covered many themes on science, history, rationality, women’s rights, the fight against superstition, the history of Beirut and the importance of trade”.

The Arab renaissance, known as the Nahda, was greatly attributed to the relationship between Beirut and Mount Lebanon. While Beirut contributed through its academic and cultural resources, Mount Lebanon offered history and experience. Many important actors in the Nahda had moved from Mount Lebanon to Beirut.

There was a major shift that led to the privatization of publishing, as print was no longer solely performed by the government and missionaries. At this point, Beirut transformed into a hub of cultural development and intellectual dialogue as it housed a growing publishing industry. The same was true for Egypt, which was greatly attributed to the rise in newspaper publishing as it had over 400 periodicals, and over 200 in Lebanon during this period.

Newspaper publishing opened doors to shaping public opinion and spreading information, including nationalist ideals, amidst an era of sociopolitical change.

The Arab Nationalist Movement and post-independence

The press was used as a medium for freedom of expression, in order to encourage the quest of independence from colonial rule. The region had been under French and British rule following the fall of the Ottoman Empire. After gaining independence in 1943, Beirut became known for having the most liberal publishing industry in the region, with many newspapers, periodicals, journals that were being published in three different languages.

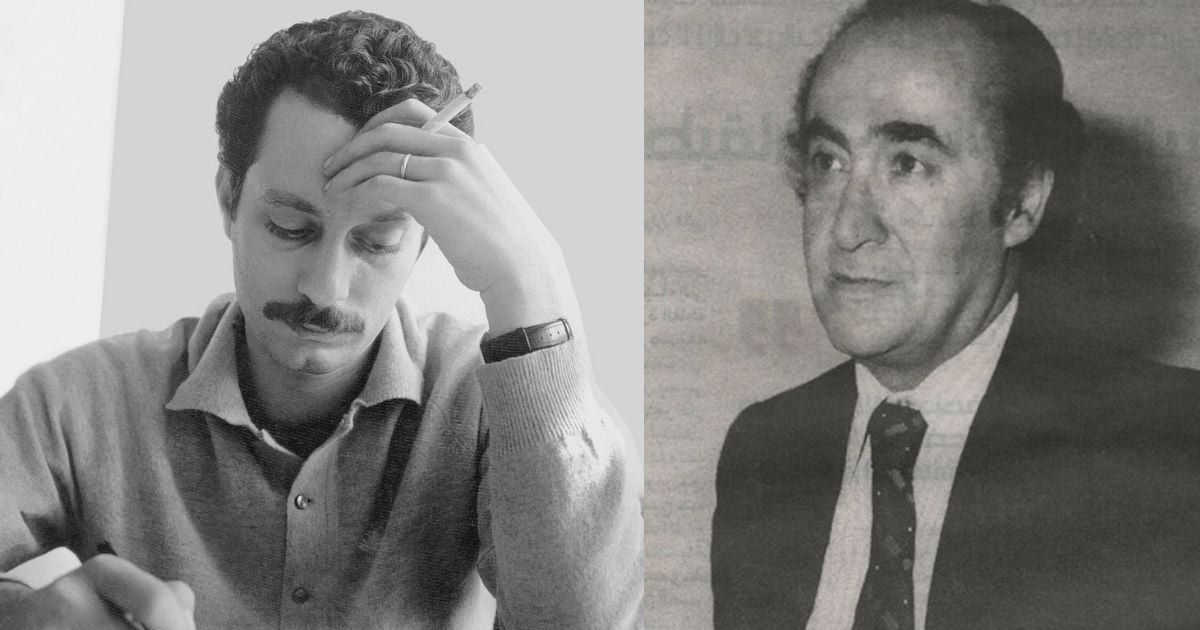

Following the Nakba in 1948, many Palestinians sought refuge in Beirut. This includes a number of scholars and intellectuals who worked to publish Palestinian resistance literature from Beirut. Its cafes were often occupied by such scholars, including Ghassan Kanafani, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Tawfiq Sayegh, and many more who had been exiled from Palestine but continued to use writing as a form of resistance from Beirut.

The Press Law

The Press Law, which came into effect by President Fouad Chehab in 1962 and had since undergone amendments in later years, stated that “The printing press, the press, the library and the publishing house and distribution are free, and this freedom shall only be restricted within the scope of the general laws and the provisions of this law.”

Source: Ministry of Information.

Though the law still majorly regulates printed media in the country, Lebanon today continues to face multiple obstacles when it comes to expressing journalistic freedoms. A great deal of journalists have faced legal difficulties over the past few years for calling out governmental negligence and injustices.

Major sources used:

Resistance Literature and Occupied Palestine in Cold War Beirut