“The Good, The Bad, The Sexy, and The Horrendous”: Interview with Marwan Kaabour, Author of The Queer Arab Glossary

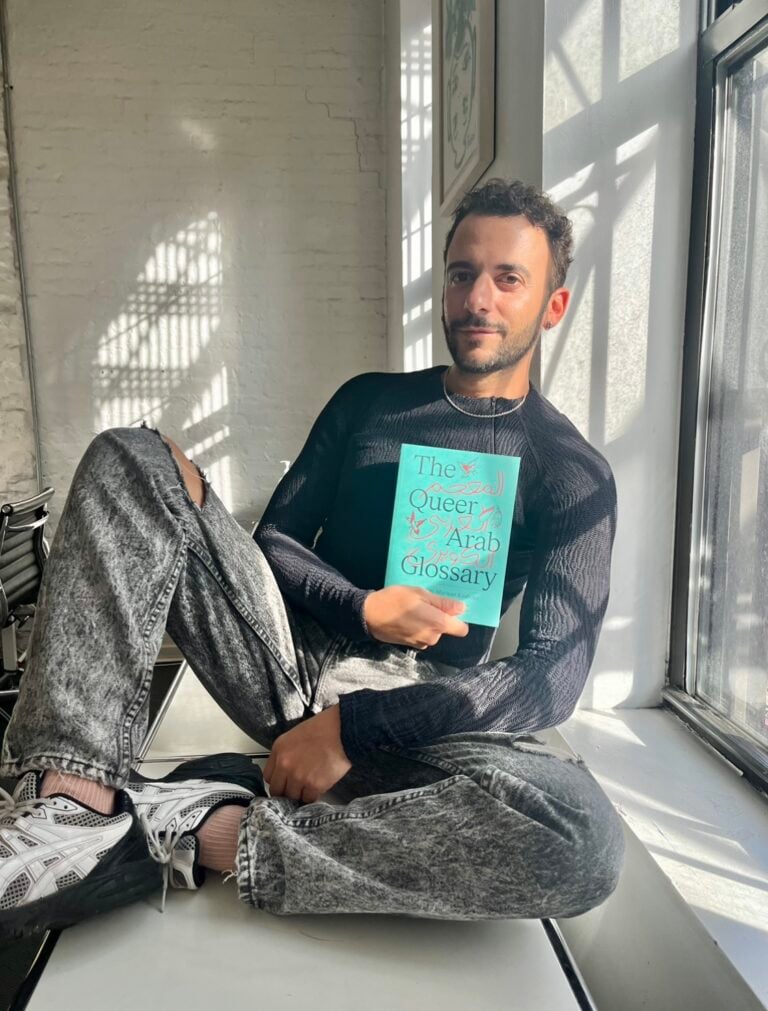

In this tell-all interview, Marwan Kaabour gives us the inside scoop on his childhood, Takweer, and his debut book The Queer Arab Glossary (2024).

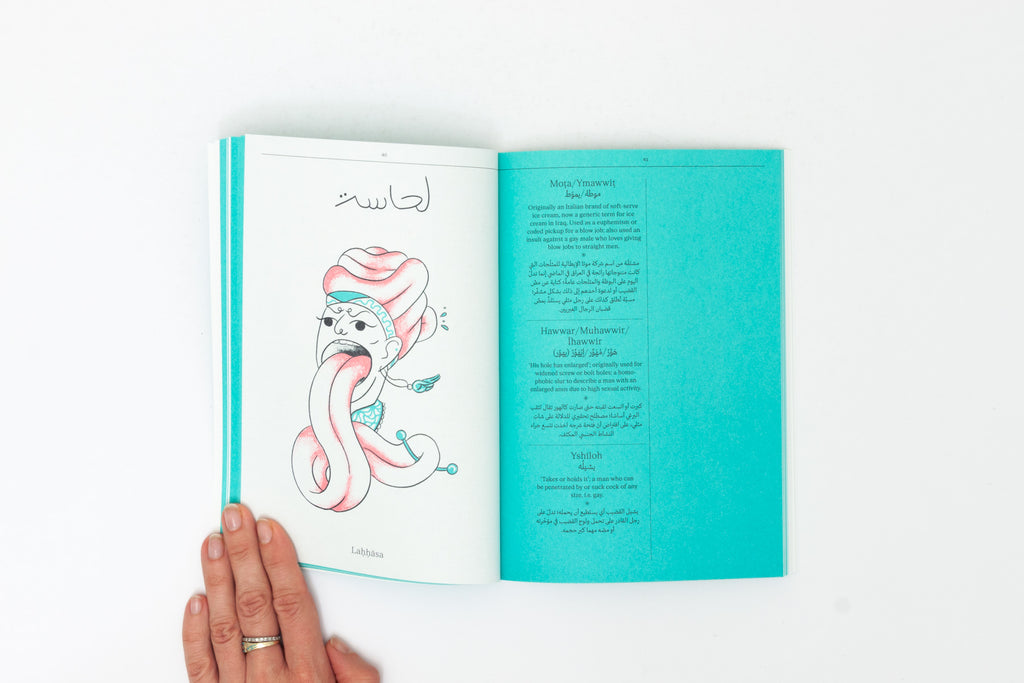

The Queer Arab Glossary is the first published collection of queer Arab slang. This glossary captures the lexicon of the Queer Arab community with all its quirks and diversities. It contains over 300 words ranging from “the good, the bad, the sexy, and the horrendous.”

Growing Up Queer & Early Career

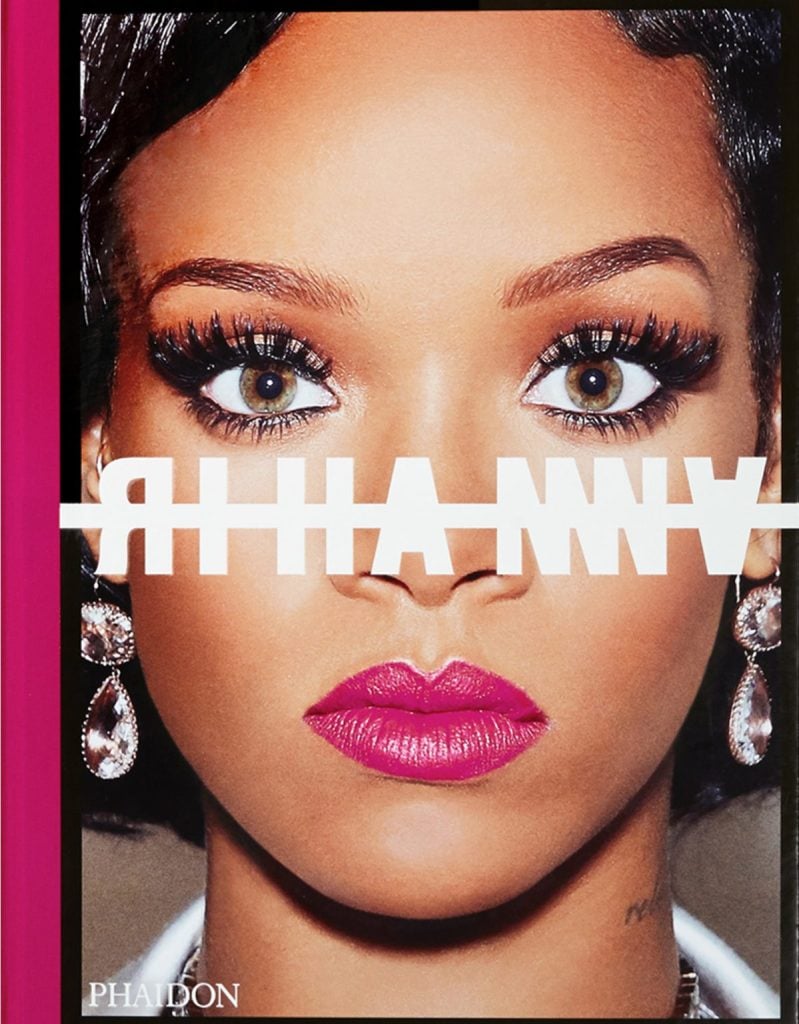

The cover of Rihanna’s photo book, designed by Marwan Kaabour.

Kaabour grew up with two artists as parents. His father was a musician and actor, and his mother was a painter. When the time came for Kaabour to apply to university, he applied to both theater and graphic design. These majors encapsulated both sides of his personality. Kaabour reminisced on his work as a child actor working in television, most notably the period drama Al Raghif, as well as on a series of commercials.

Kaabour studied graphic design at AUB then moved to London in 2011 to pursue his master’s degree. At his core, Kaabour is a storyteller. His passion for graphic design stems from the medium’s ability to tell stories through a multitude of facets. Kaabour has been practicing as a graphic designer for around 15 years, particularly in collaboration with a multitude of institutions. Over time, Kaabour realized his niche in graphic design lies in publication, from small, experimental artbooks to leading the design of the 2019 Rihanna photo book. Kaabour has designed over 20 books over the course of his career.

In 2019, Marwan launched Takweer, an online platform on Instagram exploring queer narratives in Arab history and pop culture. The name “Takweer” is a play on the Arabic word takwir (تكوير), and the English word queer. Kaabour views Takweer and its projects as a way to use the tools he learned in graphic design. It is also a way to create non-commercial content that fosters community building.

The Making of The Queer Arab Glossary

As Takweer’s first realized project, it arose from Kaabour’s growing frustrations around the Arab queer communities’ disconnect from Arab culture and language. Their reliance on Western queer culture as a crutch to define themselves added to this frustration.

Marwan went on to say: “We speak about Stonewall as if it’s our history, we speak about Marsha P. Johnson as if she’s our martyr. By all means, these are part of our collective queer memory but what about our stories, our people, our heroes, and our tragedies.”

The idea of the book started with Kaabour’s interest in language and linguistics. The self-proclaimed linguistic geek became fascinated by the etymology of words, a passion he adopted from his own father.

As Takweer grew, Kaabour began engaging more with the page’s followers. He would have conversations with them in DMs or comment sections, about their experiences growing up queer and Arab. As these conversations went on, Kaabour would take note of words people used in their own dialect. This led to Kaabour posting an Instagram prompt asking Takweer’s followers to submit Arabic queer slang that they used. These would be accompanied by the dialect the terms originate from and their definitions. After repeating the prompt several times, Kaabour found himself with a spreadsheet filled with over 300 words.

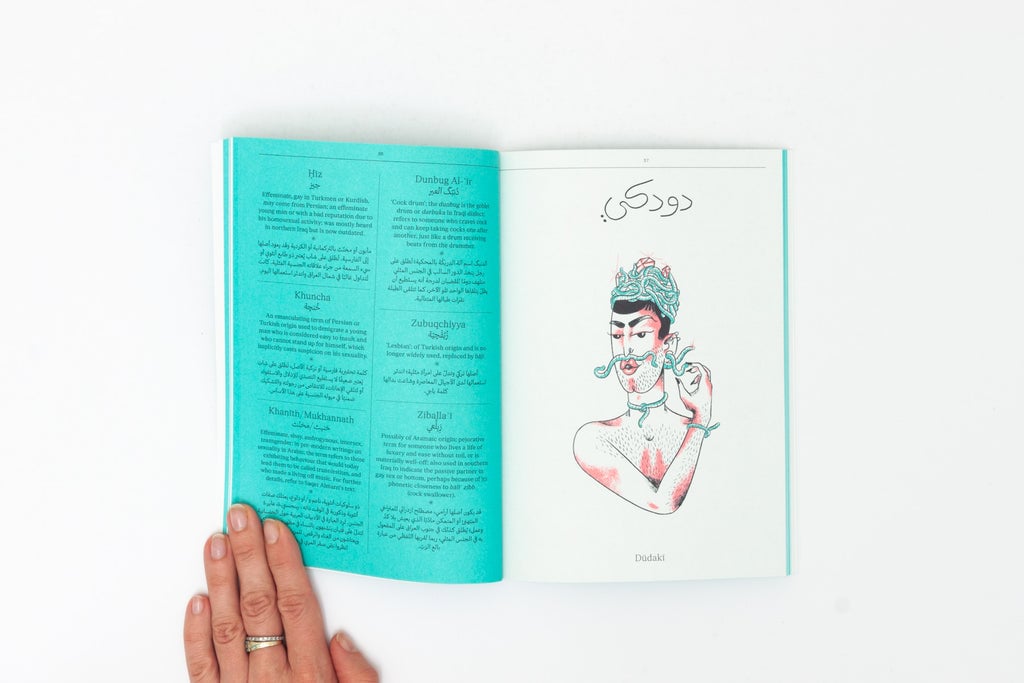

For the four years that followed, he engrossed himself in researching the history of these terms. The end result is a publication that is part illustrated glossary, divided into six dialectic sections (Levanitne, Iraqi, Egyptian, Sudani, Gulf, and Maghrebi), and part anthology of eight texts by leading thinkers of the region.

Acknowledgements

One aspect acknowledged is the lack of female queer terms in the lexicon that are not centered around men. Most words in the queer arab lexicon define queer women by their proximity to men or masculinity.

When asked if The Queer Arab Glossary could inspire the creation of new slang that de-centers men, Kaabour said “I hope so, first of all I think words will come into existence whether the book is there or not. Young people, who are like the main drivers of the production of slang. With every generation comes a new vocabulary, all the time, with different political, social and cultural changes, so new words will inevitably be born. However, I do hope that my book can generate a conversation that can lead to a certain language to be born that addresses a particular gap, whether that be the experience of queer women or people who fall outside of the binary.”

Kaabour then went on to say “I think, maybe, there’s a case for us to take back ownership of a lot of this language that many might deem as derogatory of loaded with trauma and try to adopt it as words that can speak more authentically to our experience as queer Arabs. Much like the word ‘queer’, the word queer historically was a derogatory term, it only very recently became adopted as a mainstream term to describe the non-normative gender and sexuality experience.” This conversation led to the discussion over the content in the book being explicit both in text and imagery.

Retrospectives and Public Perception

When asked if he had any doubts over publishing a book of this nature, Kaabour replied, “There was no question, this was the only way I was going to publish it. I am not here to censor my experience, or anyone else’s. I am here to give you the full picture, the good, the bad, the sexy, and the horrendous.” Kaabour went on to explain that he didn’t want to shy away from presenting real people’s experiences. Even if it included words that people may deem obscene or even offensive. “Sexuality, sex, and gender is not sanitized, it’s not clinical, it is complex and it is fun.”

I brought up the question of the book’s explicit content and how it had been received by Arab audiences.

He said, “The reception has been overwhelmingly positive from my experience. However, it is also important to mention that outside of Lebanon, the book is not available in bookstores in an official manner because the book would ultimately get banned. It is available in Lebanon and I’m very fortunate that is the case. I know for a fact that we’ve been in discussions with book publishers and distributors across the Arab world who love the book and would love to stock it, but they would be too scared or cautious to do that. I haven’t received any serious negative critics of the book in an informed way. However, yes, there might be a bunch of Instagram comments from randos that I do not necessarily care for. Am I going to lose sleep over what people type in the comments? I’m too old for this sh*t”.

Queering Slang

Readers might notice some of the words used in The Queer Arab Glossary are not intrinsically queer in meaning. Words like ukhti, imme, or binti found in the glossary.

When asked about the inclusion of these words, Kaabour said, “the book is a collection of slang terms used by the queer community, and by people outside the community, to speak about the queer experience. Some of those words happen to be words used by people outside of that community as well to mean something else. When I include some of those words in the book, I’m including them with the very specific description that they are used within the queer context. So a word like imme, for example, means ‘my mom’. Within the context of the queer community, immi becomes the symbol of the matriarch figure within a chosen queer family.” This is in reference to how many members of the queer community form a chosen family, often not blood related.

Future Projects

When asked if Kaabour was planning an updated edition to the glossary, he responded, “potentially, look I don’t think I’m ready just yet to update the book. The book took four years of work to bring to fruition and I think a book like this needs to exist in the public sphere for a while to allow it the chance to grow. Books are like children, they need to mature. I want to see, as the author of this book, how my relationship with language will change over time. As well as, how the queer community will change its relationship with language overtime.”

“Some time down the line, yes, I think it would be good to revisit this book and to kind of update it somehow. Would it be a book? Would it be an online archive of these words? Who knows. For now I’m more interested in how people are engaging with it. But of course I have been keeping tabs on a lot of the words I have been learning since I published the book, so there is a chance for an updated edition in a few years time. It’s a bit too early to talk about it now.”

When asked about other future projects, Kaabour stated that he was entertaining a few ideas. One of which hinted at transforming Takweer from a digital space into a physical one. This can be done through an exhibition that tells the story of Arab queerness via objects or pop culture references documented by Marwan through the page. Kaabour also expressed his interest in storytelling and oral history, “so maybe a podcast could be interesting.” He added that he would love to write something more personal, exploring Arab queerness from his own perspective.

How are you celebrating Pride Month? You might enjoy: 18 Things You’ll Understand If You’re Queer In Beirut

“Made in Beirut” Tee

High quality t-shirt that is available in either round neck loose fit made of 100% cotton with short sleeves, or fitted cropped with a round neck and short sleeves (95% cotton,5% elastane).

Groovy Tee

High quality t-shirt that is available in either round neck loose fit made of 100% cotton with short sleeves, or fitted cropped with a round neck and short sleeves (95% cotton,5% elastane).

“Made in Beirut” Tee

High quality t-shirt that is available in either round neck loose fit made of 100% cotton with short sleeves, or fitted cropped with a round neck and short sleeves (95% cotton,5% elastane).

Groovy Tee

High quality t-shirt that is available in either round neck loose fit made of 100% cotton with short sleeves, or fitted cropped with a round neck and short sleeves (95% cotton,5% elastane).