Between Concrete and Steel: The Beirut Green Project

Lebanese citizens have become accustomed to the constant and consistent construction of “bigger and better” concrete and steel buildings and malls in the country. Though these establishments offer shopping, dining, movie-watching, and (when you can afford it) homes to inhabit, the enjoyment they provide is not without a cost: Lebanon is severely lacking in public green spaces for people to enjoy. In response to the search for green amid a gray city, the 2011 Beirut Green Project sprouted.

After spending three years in Paris and walking through its parks as part of her daily routine, Lebanese freelance motion designer Dima Boulad found Beirut to be disconcertingly gra y. Three of her colleagues–Rana Boukarim, Nadine Feghaly, and Joseph Khoros–realized that they all shared in the frustration of the utter lack of public green places in the city.

(Image via Facebook)

As a result, on World Environment Day in 2010, the four friends chose to put a square-meter of greenery in nine spots around Beirut, with a wooden sign reading ‘Enjoy Your Green Space.’

“As a Beirut citizen, I have access to 0.8 square meters of grass in my city. This is very little,” Boulad told Beirut.com. “The World Health Organization says a city should have a minimum of 9 square meters per person in order to be considered healthy.”

The humble but bold initiative drew a great amount of attention, and people responded encouragingly, sharing photos of the patches of green on social media and conversing online and by word of mouth about their support of the project.

A year later, another peaceful protest called, “Green the Grey,” took place with Boulad, Boukarim, Feghaly and Khoros inviting people to a “pop-up park.” Beirut’s Sassine Square was covered in grass for a day. Boulad mused that the positive feedback received after that event led to the birth of the Beirut Green Project initiative, made official in 2011.

Green spaces are important for a myriad of reasons. Firstly, the environmental benefits are huge, as green spaces clear up the air, and they provide places for people to exercise. However, despite these factors, Boulad notes that for the BGP, there is difficulty convincing people on the importance of their initiative, noting that people often compare it to “bigger” problems that need fixing and treat it as a secondary concern. However, it would appear that many of the so-called “bigger” problems can benefit from green space, which has been shown to lowers violence rates, encourage tolerance, and provide a means of stress-relief that many people living in Lebanon may desperately need. Moreover, it gives people an opportunity to interact with one another.

Boulad draws a picture: if a child from one neighborhood plays with a child from another neighborhood, a butterfly-like effect could end up occurring and making an important impact on a larger level, as this public space has suddenly taught diversity, and makes the statement that “you’re not like me, but you’re still enjoying this park with me. You’re still another citizen,” explains Boulad.

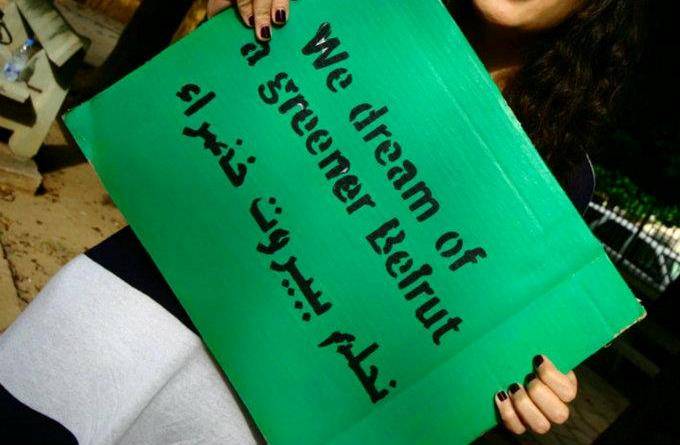

(Image via Facebook)

But just how many available green spaces are there in Lebanon? Twenty-four, it turns out-even though it’s not enough, it’s still more than people think. Boulad commented that there is nothing to highlight these places for the public to truly notice them. The Gebran Khalil Gebran garden, located in the downtown area, for example, has walls surrounding it, effectively closing it off to the public.

The Beirut Green Project offered one solution to building awarenes through a website dedicated to directing the pubilc to parks – large and small – in Beirut, from the better-known (Sanaya, Gebran Khalil Gebran) to the lesser-known (Mufti Hassan Khaled garden, Walid Eido garden) spaces. It also provides each park’s available facilities (pet friendly, wifi service, etc), the number of benches, and a little background information on each. It proves to be a very handy guide for anyone who wants to explore the greenery this city has to offer.

When asked about the Beirut Green Project founders’ hopes for the future, Boulad said, ” it becomes a pressing issue on every politician’s agenda. It’s a right, not a privilege, for a citizen to have access to the green space. We need more people to say so.”

As a final piece of advice, Boulad encourages people to make use of green spaces. “If you want to run, for example, if you want to have a celebration somewhere–why not do it in a park? We need to take care of our gardens, because they aren’t going to stay forever if we just ignore them. We all have to join hands and say ‘this is not enough.’ This is our message.”

1